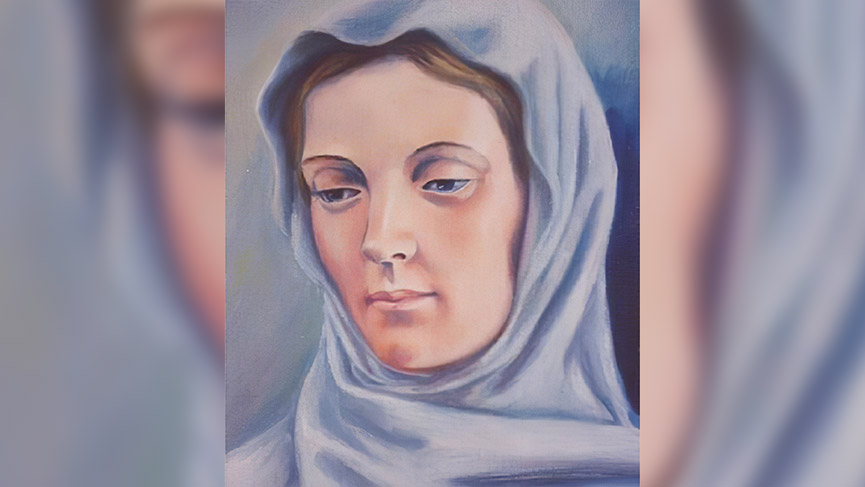

Jeanne Le Ber, the Angel of Ville-Marie

Montreal

Here is a text written by Fr. Marcel Lessard highlighting the life of Jeanne Le Ber. She was North America’s first religious recluse.

On Ville-Marie soil, where “Marguerites” have figuratively bloomed for more than a century (from Marguerite Bourgeoys to Marguerite d'Youville), the intrepid Jeanne Le Ber was born, and came to be known as the recluse who “fought on all fronts”1 . Do you know of Jeanne Le Ber? Her name may suggest that of an ordinary religious who devoted her life to prayer. Le Ber, however, was far from ordinary, becoming the first religious recluse in Canada and known for her courageous faith. Her story begins with her roots, the second child in a family of five children.

She was born on January 4, 1662. She had an older brother, Louis, and three younger brothers, Jacques, Vincent and Pierre. Her mother's name was Jeanne Le Moyne, married to Jacques Le Ber, a rich merchant from Ville-Marie. The young family was very religious and set up their home on Saint-Joseph Street (which would later become Saint-Sulpice Street) opposite the Hôtel-Dieu Hospital. Her godmother was Jeanne Mance, who had just founded the Hôtel-Dieu and had welcomed three Hospitallers of Saint Joseph to lend her a hand. She did not know her godfather, Paul de Chomedey, who left the colony when she was barely three years old. She was, in her formative years, the portrait of a happy and energetic little girl.

Her family soon moved to Saint-Paul Street, to a house adjacent to that of her uncle, Charles Le Moyne and aunt, Catherine Primot. Their family of eleven boys and three girls (two had died in infancy) shared a household full of boisterous play, a part of their daily family life, through both the joyful and the difficult times. It is easy to imagine a young Jeanne playing pretend soldier-games with her cousin, Pierre Le Moyne, in the middle of winter, amid the laundered white sheets stretched out to dry throughout the house. Five months his junior, her influence will have helped nourish a healthy alliance and beautiful tenderness with the soon-to-be soldier, explorer and future Sieur d'Iberville. But as she matured in intelligence and conscience, her curiousity grew, leaving her to question many things.

By the age of five, she would routineley cross the street to share a snack with her godmother and the other hospital workers at the Hôtel-Dieu. A few years later, at the age of 12, her father brought her to Quebec City where her aunt Marie Le Ber, who had become an Ursuline nun, welcomed her at the Ursulines Community. The teenager had developed a close bond with her aunt, who had since become a reputable teacher and known for her excellent embroidery skills.

Having returned to the family home by the age of fifteen, she continued to learn domestic skills from her mother. Though her godmother had died four years prior, Le Ber remained friends with her neighbours, the religious. She had grown into a young woman, and considered by many at the time as 'a good match' befitting her status: attractive, healthy, independent and well-off. Her father had hoped to marry her to a young local bourgeois. But a secret longing had developed in her heart. She sensed that God had 'chosen the better part which will not be taken away' (Luke, 10:42). By eighteen, she confided to her parents the growing desire to live a more spiritual interior life.

She felt called to a life fully consecrated to God through silence and perpetual prayer. She felt the call to become a recluse, and nothing less! With the permission of her spiritual director, Mr. François Séguenot, whom she had come to know in Quebec City, she took her vows of chastity and reclusion for five years. While the city was still asleep, the recluse would leave in the early morning hours to go to Mass. Her days were spent in prayer, embroidery, sewing, and reading. Little by little, her reputation as a virtuous and prayerful woman had spread throughout the small town of Ville-Marie. She was entrusted with prayer intentions for healings, financial transactions and military protection before the Natives and the British. Her role is often compared to that of Sainte Geneviève who, at the gates of Lutèce (Paris), was concerned with protecting the people from an attack by the Huns2 . She is now known as “the Angel of Ville-Marie”.

Having contributed to the construction of a chapel for the convent of the 'secular girls' of the Congregation of Notre-Dame, she obtained the favour of having a reliquary built, which opened a window on the choir and the tabernacle of the chapel. She was able to move in on August 5, 1695, the feast of Our Lady of the Snows. Following a ceremony in the church, which was celebrated by Fr. Dollier de Casson, a procession was held towards her reclusory from which its doors would be closed behind her forever. From then on, she spent her nights adoring Him whom she described as “her magnet”. In this way, she would be “the lamp of the sanctuary”, burning with love before her Lord. She died on October 4, 1714 at the age of 52, after 34 years of seclusion and contemplative prayer. The young colony was upset to lose the prayer of intercession of the one who was called “the Angel of Ville-Marie”. The funeral eulogy given by Fr. François Vachon de Belmont recognized the model of virtue and Marian devotion left by Jeanne Le Ber, proposing it for our prayers.

During this time of pandemic, we thank the generous care of our 'guardian angels' on earth: merited human recognition. But let us not forget to turn our eyes to the one who implores Mary to continue to watch over 'her' city. She is still the 'Angel of Ville-Marie' for us today. The tomb of Jeanne Le Ber rests in the nave of the Chapel of Notre-Dame-de-Bonsecours. We will soon be able to visit her and entrust ourselves again to her intercession.

Fr. Marcel Lessard

Please find this new prayer, written by Johanne Biron

1- Deroy-Pineau, Françoise, «Jeanne Le Ber, le recluse au cœur combats », Montréal, éd. Bellarmin, 2000, 193 pages

2. Gallo, Max. « Geneviève de Paris. Lumière d’une sainte dans un siècle obscur » Paris, éd. XO, 2013, 152 pages.

Comment

Comment

Add new comment